CANDLESTICK PARK MEMORIES

Billy McD slipped his mother’s Dodge Dart into the red zone beside South Sunset playground where a heated three-a-side basketball game was in progress. He stuck his muddled mop of red hair out the car window and yelled in his lovely Irish lilt, “Hey lads, I’m goin’ to the Niners game. Who’s wit’ me?”

It was a rare Saturday contest at Candlestick Park, the final game of the 1972 season. The 49ers needed a win over the Minnesota Vikings, led by Pro Bowl quarterback Fran Tarkenton, to sneak into the playoffs.

Within minutes five sweaty teenagers Mickey Fitz, Big O, Young Murph, John L and myself, were at the Dodge’s doors, shoving and arguing over the shotgun seat. We had a pocketful of quarters and an odd assortment of baseballs, footballs and basketballs, but not a single ticket to the game.

The route to Candlestick from South Sunset, at 40th and Vicente, was a mystery to me. Billy, the senior member of the crew, was 16 years old and a newly licensed California driver. He stood a tad over five feet tall and was lovingly known as, “the Munchkin of County Mayo.” He claimed he knew the way to the stadium.

“I thought your mom said you couldn’t drive past 19th Avenue,” I said. Munchkin shot a nervous scowl my way and hit the gas.

Forty minutes later we were miraculously on Jamestown Ave. The Candlestick carnival loomed dead ahead. Traffic thickened. Ticket scalpers barked at us from street corners. On the car radio 49ers broadcaster Gordy Soltau gushed about Tennessee Ernie Ford’s rendition of the National Anthem. He claimed Bruce Gossett was loosening up for the opening kickoff.

“We need a few bucks to park,” Munchkin said frantically.

In the back seat we counted our change. “Three dollars and seventy five cents. That’s all we got,” I said.

Munchkin suddenly snapped the steering wheel to the left and shot down Ingalls, a side street off Jamestown. An elderly man with a wild, Jimi Hendrix-style Afro waved us into a driveway. “It’ll cost you $4 to park here,” he said. I offered him $2 and a scuffed baseball signed by San Francisco Giants second baseman Tito Fuentes. He snickered contemptuously, cussed under his breath, then reluctantly agreed.

As we jogged the five blocks to Candlestick a light drizzle began to fall. We were unprepared. No jackets.

“Meet in the end zone at half time,” Munchkin said. “Section 11, right behind the dugout.”

We all knew the drill. We were on our own now. My mission was to find Mr. Ryan, a kind-hearted ticket taker who also served as a little league baseball umpire. Every young player in The City had heard Mr. Ryan’s distinctive “STEEEEE-RIKE THREE” call at one time or another.

We split up and I wandered through the Candlestick parking lot salivating to the smell of grilled onions and sausages. A handful of ticketless tailgaters lounged in folding chairs listening to Lon Simmons’ play-by-play calls on KSFO.

Near Gate F I spotted Mr. Ryan collecting tickets. I waved. He saw me and put up his hand like a traffic cop directing cars to a halt. I paced for several anxious minutes while keeping an eye on Mr. Ryan. When the crowd cleared he gave me a nod and I sprinted to the turnstile.

“Go on now. Get in there. Don’t cause no trouble,” he said. Then he handed me a red and gold 49ers keychain. It was a plastic giveaway. I was ready to toss it in the trash. Mr. Ryan noticed and said, “Hold on to that. It might bring us luck.”

The first half was nearly over as I made my way past beer vendors and hot dog stands to Section 11. I didn’t miss much. Gossett had kicked two field goals for the 49ers and Minnesota held a 7-6 lead after Tarkenton’s touchdown pass to Ed Marinaro.

Late in the third quarter I found Munchkin and the boys stuffing themselves with peanuts behind the baseball dugout in section 11. The Vikings had widened their lead over the 49ers to 17-6. Much of the end zone crowd had departed, probably due to the 49ers lack of offense and the steady light rain. We found a handful of empty seats along the railing and claimed them for ourselves.

John Brodie, who had been sidelined with injuries most of the season, warmed up on the 49ers sideline and prepared to replace Steve Spurrier at quarterback. I pulled out my souvenir keychain.

“Mr. Ryan gave this to me. Did you get one?” I passed it to Munchkin.

“No. Came through Gate A,” he said. “Officer Busalacchi let us in.”

Midway through the fourth quarter the 49ers were in desperate trouble. They began a drive from their own one-yard line. From our seats we could barely see Brodie huddle the club at the opposite end zone over 100 yards away. We shivered in the cold rain and entertained ourselves by throwing peanuts at one another. We were ready to hit the road, hop in the Dodge Dart and crank up the heater.

And that’s when Brodie suddenly breathed life into the 49ers. He started by completing a 12-yard pass to rarely used running back John Isenbarger. Then he went deep for 53 yards to Munchkin’s favorite player, Gene Washington. Brodie capped the magical six-play, 99-yard drive with a 24-yard scoring dart to Washington.

I tackled Munchkin and we rolled down the damp concrete aisle. Under the chaotic dogpile I heard Munchkin’s muffled moans. He didn’t think it was funny so I pulled him to his feet and brushed the peanut shells from his bushy red hair.

The 49ers still trailed 17-13, but now there was a noticeable spark on the sideline and in the stands. With 1:35 to play the 49ers forced a Vikings punt and took over again at their own 34-yard line. They were 66 yards from paydirt and in need of a touchdown to claim their third straight NFC West title.

“Hey Munchkin, give me that keychain,” I said.

“Naw, I’m keepin’ it. This thing’s good luck,” he said. Munchkin took the talisman in his right hand and quickly made the sign of the cross.

As if on cue, Brodie completed three passes. Suddenly, the 49ers were at the two-yard line directly in front of our end zone seats. Then Brodie misfired on two straight passes and just as quickly the crowd went silent.

Third down with 25 seconds to play. The tension was unbearable. Munchkin fidgeted and chewed on the plastic keychain. I closed my eyes and prayed. Brodie broke the huddle and walked coolly, confidently toward the line of scrimmage. He scanned the Vikings defense, looking left then right. From our seats we could hear the call, “Y HOT, Y HOT” as he placed his hands under Forrest Blue, the 49ers center.

Brodie took Blue’s snap and rolled right. He continued to drift right… right… right seemingly forever. We were on our feet. Brodie waved his left hand, motioning tight end Dick Witcher to break to the right side of the end zone. I watched speechless and numb as Witcher broke out of the pack and into the clear.

“HE’S OPEN,” Munchkin screamed. “THROW IT. NOW. THROW IT.”

Brodie did. TOUCHDOWN 49ERS! Candlestick Park erupted into a deafening roar.

Munchkin impulsively vaulted over the railing and onto the field. He looked back at me then sprinted toward Brodie. I followed cautiously thinking the police would be waiting. Then I realized hundreds of fans were running onto the field behind me. The delirious crowd descended on Brodie, spontaneously hoisted the startled quarterback on its collective shoulders and carried him triumphantly toward the 49ers sideline.

Munchkin was in the middle of it. I could see the unmistakable euphoric grin on his face as he skipped along clutching Brodie’s leg with his left hand and the lucky key chain in his right.

Fast forward over 40 years later. It’s the opening night gala for the 49ers Museum presented by Sony. John Brodie strolls through the Museum and sees numerous artifacts from his 17-year career. He’s reminded of that 1972 49ers-Vikings game. I sheepishly tell him I was in the crowd that carried him off the field. The Bay Area boy, who was born in San Francisco and played at Oakland Tech and Stanford University before quarterbacking the 49ers, beams emotionally and says “that was one of the highlights of my career.”

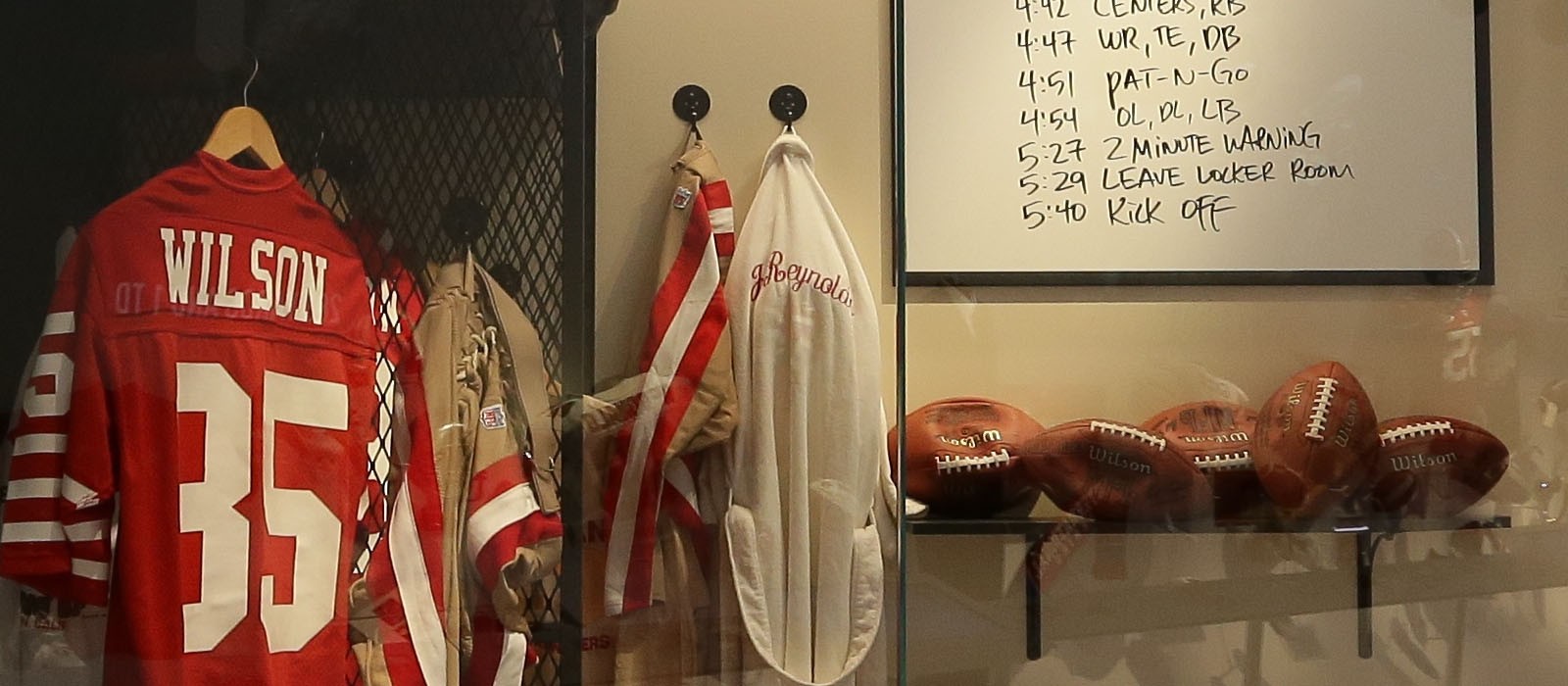

Candlestick Park is nearly gone but relics from the stadium, including lockers, seats, ticket-taker boxes and turnstiles can be seen at the 49ers Museum presented by Sony. Guests also can see artifacts from John Brodie’s storied career, including his 1970 NFL Player-of-the-Year trophy and his life-size statue in the Edward J. DeBartolo Sr. 49ers Hall of Fame gallery. There is also a re-creation of Coach Bill Walsh’s office and a Super Bowl gallery where the club’s five Lombardi trophies are on display. For more information on Museum tickets, hours and content, visit levisstadium.com/Museum. For group pricing call 415-GO-49ERS

By Joe Hession, 49ers Museum Historian