Sports figures in the Bay Area spurred social change that impacted the nation and the world. This exhibit examines five stories where the message met the moment, and sports figures intersected with social issues to create cultural touchstones and push movements forward.

Housing Discrimination in “The City”

Housing Discrimination in “The City”

Housing Discrimination in “The City”

In the summer of 1957, Major League Baseball’s New York Giants announced they were moving their acclaimed club to San Francisco. Willie Mays, then a 26-year-old star with the Giants, and the 1954 National League MVP, set out to embrace his new home.

“You have to realize that in 1957, when the Giants moved to San Francisco, baseball was literally the national pastime, it was the number one sport,” said Dr. Harry Edwards, Professor Emeritus of Sociology at University of California, Berkeley. “You had the greatest player (Willie Mays), the hero of the 1954 World Series as part of that team and without him, the Giants don’t move to San Francisco. He had to sign off on that.”

In New York City, Mays was a neighborhood icon well known for his community involvement with kids. He played stickball in the streets with local teenagers, treated entire city blocks to ice cream and welcomed youngsters to drop by his house on birthdays and holidays, particularly Halloween. Willie, and his wife Marghuerite, hoped to find a comparably welcoming neighborhood when they moved to the west coast.

While looking at housing options in San Francisco the couple settled on a beautiful, three-bedroom dwelling in an upscale, tree-lined neighborhood near Forest Hill. Little did the Mays family know their choice of real estate would soon stir up a social uproar.

Within days a well-known Bay Area home builder and property owner living a few doors away from the Mays’ chosen home decided the new neighbor might put his investments in jeopardy. He told reporters, “I happen to have a few pieces of property in the area, and I stand to lose a lot if colored people move in.” (Willie Mays.The Life.The Legend. By James S. Hirsch p. 277)

Although Willie downplayed the comment and tried to minimize the simmering controversy, Mrs. Mays recognized a subtle form of racism was at work. She told reporters, “Down in Alabama where we come from, you know your place. But up here, it’s all a lot of camouflage. They grin in your face and deceive you.” (Willie Mays.The Life.The Legend. By James S. Hirsch p.278)

Despite his athletic fame and accomplishments Willie encountered what numerous people of color have experienced while trying to find a home: racism, undergirded by social and legal constructs.

According to Dr. Michael Omi, an Associate Professor of Ethnic Studies at University of California, Berkeley, “One’s fame and celebrity does not necessarily inoculate one from pernicious racism.”

San Francisco, although celebrated as a welcoming and progressive city, remained segregated through much of the 20th century. As the city grew after World War II, a large majority of the African-American population settled in the BayView/Hunters Point area or in the Western Addition.

Dr. Harry Edwards noted that the form of racism experienced by Mays was not uncommon. Although Mays was a well recognized sporting hero, praised and adored for his actions on the baseball diamond, his presence as a homeowner in the city’s tonier enclaves was considered unacceptable.

Mays, “a superstar athlete had the audacity, the courage to go to a restricted area and tried to purchase a home in the city, which had accepted his team but did not accept him as a fully legitimate citizen or even human being,” Edwards said. “They did not want to rent to him. And so that became a headline. That became a cause célèbre and out of that cause célèbre was generated during the civil rights era, a movement for open housing.”

Terry Francois, a prominent Black attorney who later became a powerful force on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, intervened on behalf of Mays. Within days, the homeowner had a change of heart and, despite being berated by neighbors, announced he would sell to the most prominent and recognizable athlete ever to live in the area.

The area remained almost exclusively white, but Mays cracked open the door for people to see San Francisco’s segregated housing situation.

“It all came to fruition two years later in 1959 and 1960,” Dr. Edwards said. “And by 1963, the state of California had passed the Rumford Fair Housing Act. That was five years before Lyndon Baines Johnson sponsored the National Fair Housing Act (1968). But it all went back to Willie Mays.”

Although Mays initiated the small steps needed to start a long journey, housing segregation continued in San Francisco. For more information on Mays’ difficulty in purchasing a home in San Francisco see:

Chronicle Covers: When Willie Mays was denied housing because he was black (sfchronicle.com)

Willie Mays Had a Hard Time Buying a House in San Francisco (socketsite.com)

Discrimination, S.F. style, hit Mays – East Bay Times

Streetwise: Willie Mays – Western Neighborhoods Project – San Francisco History (outsidelands.org)

African American Segregation in San Francisco – FoundSF

FACTORS LEADING TO HOUSING SEGREGATION

REDLINING

Imagine a group of bankers, lenders and government surveyors gathered around a city map and armed with colored pencils. Their mission: to determine what neighborhoods were financially unstable, thus resulting in its residents being unworthy of loans and losing any chance at upward mobility.

That’s how the insidious practice of redlining began.

In the 1930s the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) used their colored pencils to grade neighborhoods and designate certain areas across the United States as unsuitable for loans. According to the color-codes used by the HOLC, green indicated an area that was “best suited,” for loans, blue meant “still desirable,” yellow for “definitely declining” and red was “hazardous.”

Members of the “redlined” or “hazardous” communities obviously felt the harshest impact. They were considered credit risks by local lenders, generally because of their racial and ethnic backgrounds, and were denied loans or were unable to obtain mortgage insurance. The dream of buying and owning a home became virtually nonexistent for them. Redlined neighborhoods in San Francisco included the Western Addition, Bayview/Hunters Point and Chinatown, areas consisting largely of African Americans and Asian immigrants.

Growing up and living in segregated areas can lead to a number of problems according to social scientists. Where an individual resides is a prime indicator of that person’s success or failure in terms of education, employment and future earnings. In segregated areas, the population is profoundly shaped by the quality of its schools, housing options, shopping centers and public resources.

“Neighborhoods have an enormous impact on a resident’s potential economic development, their mobility and their success,” Dr. Omi said. “There are some economists who are recently showing that families who moved from a high poverty neighborhood to a low poverty neighborhood, really improved their children’s economic success in terms of college attendance rates and their subsequent earnings as adults. So where one lives has a profound effect on shaping the well being and life chances of its residents and their children.”

While the HOLC was determining who was worthy of a loan, the Federal Housing Administration, starting in the 1930s, became involved with contractors and builders by subsidizing the mass-production of suburban homes. As veterans returned from World War II, they soon married and sparked a baby boom. The young families generated a new demand for housing in America. But most of the new subdivisions came with a caveat. They were available almost exclusively to whites and often came with a restrictive covenant that barred the sale of property to Black buyers.

As late as 1950, the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ code of ethics stated that “a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood … any race or nationality, or any individuals whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values.” (Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic)

The HOLC, a federal agency, seemed to agree. It insisted that any property it insured be covered by a restrictive covenant:a clause in the deed forbidding the sale of the property to anyone other than whites.

For more information on redlining in America see:

https://hoodline.com/2014/06/a-history-of-redlining-in-san-francisco-neighborhoods/

https://slate.com/human-interest/2014/05/where-to-find-historical-redlining-maps-of-your-city.htmlhttps://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

RESTRICTIVE COVENANTS

Restrictive covenants were devised to inform home owners what they can and cannot do with their property and are generally found among the “Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions” in a home’s preliminary title report. For example, restrictive covenants may state the owner must maintain and trim his front lawn, or that the owner is not allowed to raise farm animals on the property.

Racist restrictive covenants also found their way into the documents and by the 1930s became fairly common as a way of prohibiting nonwhite people from purchasing or occupying land in certain areas.

An example of a racist covenant that appears on a Redwood City, CA property title report for a home built in the 1930s states “No person of any race other than the Caucasian or white race may use or occupy the property,” with the exception of “domestic servants of a different race domiciled with an owner or tenant.” (Marisa Kendall, Bay Area News Group)

Similar racist covenants are still included on numerous property deeds across the country. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial covenants were unenforceable. The landmark civil rights case, known as Shelley v. Kraemer, addressed the plight of the Shelleys, a Black family, who migrated from Mississippi to St. Louis, MO. They purchased a home in St. Louis from a person who did not want to enforce the racial covenant. A white neighbor objected, sued the Shelleys, and won the case. The Shelleys appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which allowed the sale and ruled the state could not enforce racial covenants because they violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Nevertheless, the covenants remained commonplace, and were condoned through social enforcement and peer pressure. Then in 1968 Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Fair Housing Act explicitly made the covenants illegal.

For more information on restrictive covenants and how to remove them see:

https://www.dfeh.ca.gov/legal-records-and-reports/restrictive-covenants/.

Marisa Kendall wrote an encompassing piece for the Mercury News about racial covenants,mkendall@bayareanewsgroup.com

DISPLACEMENT/URBAN RENEWAL

During the 1950s, San Francisco’s Fillmore District was known as the “Harlem of the West.” Its vibrant nightclubs attracted the cream of the jazz world. On any given night jazz aficionados might find Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald or Dizzy Gillespie at local clubs like Jimbo’s Bop City or the Blue Mirror.

As a whole the Fillmore neighborhood was a lively, Black commercial hub with stately yet aging Victorian houses. It had its own community of locally owned restaurants, shops and services. There were employment opportunities and a sense of common purpose for the Black residents. But by the late 1950s and 1960s the Fillmore District was at the forefront of San Francisco’s redevelopment which led to widespread displacement of the Black community.

The modern concept of urban renewal originally began after World War II when President Harry Truman signed the 1949 Housing Act authorizing the rebuilding of run-down city neighborhoods. It encouraged investors or middle class buyers to purchase and gentrify property in working-class or decaying areas and generally targeted low income and not-white neighborhoods. The result was a widespread displacement of families causing a change in the area’s economic and social fabric. Essentially, Congress approved the demolition of inner city slums by providing local governments with federal funds and allowing for the seizure of property by eminent domain.

According to city planners, the Western Addition constituted a run-down or “blighted” neighborhood and was a prime area for redevelopment. By 1956 the city began to tear it down.

According to the California Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans published in 2022, the City of San Francisco closed 883 Western Addition businesses, displaced 4,729 households, destroyed 2,500 historic Victorian homes and damaged the lives of nearly 20,000 people. It turned out to be one of the largest projects of urban renewal on the West Coast.

In 1963 acclaimed author James Baldwin toured San Francisco while making a documentary for KQED entitled Take This Hammer. While driving through the Fillmore, he remarked “redevelopment” is just “the removal of Negroes.”

By the time redevelopment was completed and new housing and shops were restored, most of the former Fillmore residents couldn’t afford to return. In a little over two decades the epicenter of the city’s Black community was gone. With it went the economic opportunities and social networks for African-Americans that fostered jobs, upward mobility and community support.

For more information on urban renewal in San Francisco see:

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Sad-chapter-in-Western-Addition-history-ending-3203302.php

https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/media/ab3121-reparations-interim-report-2022.pdf

LEGISLATION

To combat housing segregation several laws have been enacted and they have gradually picked away at the restrictions and covenants that narrowed the housing options for people of color.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court case, Shelley v. Kraemer, outlawed racially restrictive covenants, yet housing discrimination continued. In many of the more affluent areas of San Francisco, like St. Francis Wood, Balboa Terrace and Forest Hills, covenants were included in purchase agreements that excluded home sellers from selling property to minorities.

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/334/1/

In 1963 the Rumford Fair Housing Act was passed by the California Legislature and signed into law by Governor Edmund G. “Pat” Brown. The bill, drafted by William Byron Rumford, Northern California’s first Black state legislator, prohibited property owners from denying housing to anyone because of ethnicity, race or religion.

https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=200320040ACR53

By 1968 housing rights became a hot potato at the national level and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act. The new law prohibited discrimination concerning the sale, rental or financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin or sex.

https://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Fair+Housing+Act+of+1968

Despite the legislation, racially-based housing segregation still exists in America. Becoming familiar with the prevalence and impact of this issue is one way to be a part of positive progress towards dismantling these constructs. The US. Department of Housing and Urban Development is a good place to start. You can also contact your local city/county government to learn more about what legislation or covenants exist in your community. Other sources include:

https://oag.ca.gov/system/files/media/ab3121-reparations-interim-report-2022.pdf

https://www.cnn.com/2022/06/19/perspectives/homeownership-gap-juneteenth/index.html

The Olympic Project for Human Rights

The Olympic Project for Human Rights

The Olympic Project for Human Rights

During the 1960s, San Jose State University was at the epicenter of the track and field world. Known as “Speed City” because of its world class sprinters, SJSU held the keys to America’s gold medal chances at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City.

At the same time, city streets from San Francisco to New York were in turmoil.

On March 7, 1965, future U.S. Congressman John Lewis, then just 25 years old, led an estimated 600 civil rights marchers across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. The main objective of their civil disobedience was to call attention to the lack of voting rights for the area’s Black citizens, and to seek the elimination of discriminatory literacy tests and poll taxes.

On the other side of the bridge Alabama state troopers, and a pack of hastily deputized local men, were waiting to disperse the crowd by any means necessary. Suddenly, the law enforcement officers attacked the marchers leaving 17 peaceful citizens hospitalized with various injuries including Lewis who suffered a fractured skull. Television news broadcasts of the event, and the bloody marchers left in its aftermath, were beamed across the nation and sparked support for the voting rights movement.

In August of 1965, Congress unanimously passed the landmark Voting Rights Act. Less than a week later rioting started when Los Angeles police performed a traffic stop then arrested a Black motorist in the largely African-American neighborhood of Watts. It ignited a week of bloodshed and arson that nearly leveled Watts, leaving 34 dead. The following summer, Chicago, Cleveland and approximately 40 other U.S. cities experienced racial unrest. Then, in 1967, chaos erupted in Newark, N.J. leaving 26 dead and 1,500 wounded. That same week rioting consumed Detroit leading to the death of 43 people, and leaving 1,000 wounded.

On April 4, 1968, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis igniting several days of violence in over 120 U.S. cities and leaving at least 46 people dead.

Two months later, on the night he won the California and South Dakota presidential primaries, Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. Kennedy, a liberal democrat and former U.S. Attorney General, campaigned on the promise of civil rights for America’s minorities.

By 1968, America was at a breaking point and seemed desperate for change and progress. Protests and riots became common events across the country with particular fervor in the Bay Area and at its college campuses.

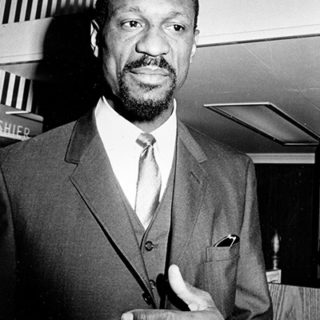

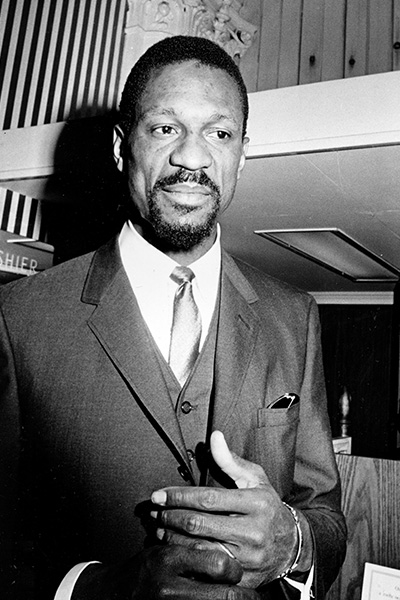

At San Jose State, Dr. Harry Edwards was aware of the plight of Black athletes and students at the university from his days as a scholarship athlete there in the early 1960s. “I had to live with the freshman basketball coach for a month,” Edwards recalled of his days at SJSU. “All the housing was segregated.”

After graduating from SJSU with honors in 1964, Edwards was awarded a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and began work on his Ph.D in sociology at Cornell University. Two years later, he returned to San Jose State as a part-time professor and discovered little had changed. The campus had few Black professors and no Black coaches. On-campus housing was scarce for African-American athletes and local landlords were reluctant to rent to them.

Elsewhere on campus, track stars and Olympic gold medal hopefuls Tommie Smith, John Carlos and Lee Evans found themselves restricted by the racial inequities that existed in housing, employment, campus social life and most significantly, academics. According to Dr. Edwards, Black student athletes were directed away from business, science and humanities and funneled into physical education or programs that kept them eligible to compete in intercollegiate sports. This form of institutional racism made it difficult for people of color to graduate with a marketable degree.

“On San Jose State’s campus, if you were Black, you could major in one of three things: physical education, probation and parole, because Blacks will always be going to prison and need some probation officers and social welfare,” Edwards said with sarcasm. “Those were the three things that Blacks majored in. I had to petition to major in sociology, which was in the same department as social work and probation and parole.”

With the 1968 Summer Olympics on the horizon, Smith, Carlos and Evans recognized they had the opportunity and platform to be a force for change and joined SJSU’s United Black Students for Action (UBSA) in September 1967.

“Smith, Carlos and Lee Evans are three of the greatest track and field athletes on the greatest Olympic team that the United States ever fielded,” Dr. Edwards said. “So they’re great athletes, winners. This is the key with athletes and their impact in terms of social change and sport. The other thing is that they were conscientiously committed to social justice.”

Almost immediately they were tested. As the 1967 school year began, the USBA, under lead organizer and spokesperson Dr. Edwards, demanded equitable changes at SJSU for students and athletes of color. In doing, so they organized the school’s Black football players and threatened a boycott. If the administration failed to meet the USBA’s demands, the African-American players would not participate in the Spartans’ 1967 season opening game with the University of Texas-El Paso.

Sensing a possible confrontation at Spartan Stadium between protesters and counter-protesters, and the threat of racial violence, SJSU president Robert Clark canceled the football game. The decision seemed to rankle law and order politicians of the day. California governor Ronald Reagan was appalled by Clark’s decision and called it “an appeasement to lawbreakers.”

“Ronald Reagan said that he wanted both me and Dr. Clark fired, and that he was going to send in the National Guard,” Dr. Edwards said. “Then, of course, the Hells Angels said we’re going to come in with guns to help support the National Guard. Then you get Black groups saying we’re going to come in to protect the Blacks. And the next thing you know, Dr. Clark said, “Harry, what do you think our options are?” I said, “This is not worth bloodshed, cancel the game.”

Reagan’s vocal reaction to the canceled game brought national publicity to USBA and its cause. The east coast media picked up on the story and the New York Times claimed it was the first time a college football game was canceled “because of racial unrest.”

Meanwhile, the track stars of “Speed City” were training for the greatest sporting spectacle of its time, the 1968 Summer Olympics. Three of the world’s top sprinters, Smith, Carlos and Evans, all members of the Spartans track team, prepared to showcase their talents in Mexico City. Off the track, they connected with Edwards who also was organizing the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) to protest racial segregation.

OPHR focused on the welfare of Black people globally and advocated for Black athletes.

Among the issues OPHR sought to rectify were:

- improving the welfare of Black people globally

- ending apartheid in South Africa and banning the country from the Olympics

- adding Black coaches to the United States Olympic team

- removing International Olympic Committee chairman Avery Brundage

- advocating for Black athletes

- restoration of conscientious objector Muhammad Ali’s boxing title

Initially, OPHR threatened a boycott by all Black athletes at the 1968 Summer Olympic Games if their demands were not met. But after discussion with several Olympic hopefuls, Smith and Carlos realized it would be unconscionable to persuade others to abandon their dreams of a gold medal.

“Many athletes thought that, ‘Man, I trained all my life to go to the Olympics,’ ” Carlos said. “I promised my kids I was gonna bring a medal home. My church is counting on me and my community’s counting on me.’ So, you know, it was kinda hard for them to bite into it… They made it clear they understood the necessity of boycotting. But it was a big chunk out of their lives to step up and say, ‘Man, I’m gonna sacrifice an Olympic gold. I’m gonna sacrifice a berth on the Olympic team.’ And we didn’t feel that we had any right to tell them that you must do this.”

When the boycott was called off Carlos initially was disenchanted and chose not to go to Mexico City. But after some deep meditation he changed his mind.

“I thought, ‘If you stay home, do you think the person that gets up on the victory stand in your place would represent your thoughts, your feelings, your vibes?’” Carlos said. “And when that came to me, man, it was like automatic. Like somebody hit a switch, and I said, ‘I’m going to the games.”

Smith also was ambivalent about a boycott and not sure it would help the Black community achieve its goal.

“There have been a lot of marches, protests, and sit-ins on the situation of Negro ostracism in the US,” Smith said in Race, Culture and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and Their Aftermath. “I don’t think this boycott of the Olympics will stop the problem, but I think people will see that we will not sit on our haunches and take this sort of stuff. Our goal would not be just to improve conditions for ourselves and our teammates but to improve things for the entire Negro community.”

UCLA basketball star Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) was one prominent collegiate athlete who decided to sit out the games.

“It was too difficult for me to get enthusiastic about representing a country that refused to represent me or others of my color,” Abdul-Jabbar wrote in his book, COACH WOODEN AND ME . ”I was grateful, but I also thought it disingenuous to show appreciation unless all people had the same opportunities. Just because I had made it to a lifeboat didn’t mean I could forget those who hadn’t. Or not try to keep the next ship from sinking.”

U.S. sprinters Smith, Carlos and Evans considered their Olympic platform through a different lens. They realized they still had an opportunity to address their concerns about discrimination and human rights before millions of spectators.

“I had a button on my sweatpants, a sweat jacket and then I had the button on my jersey. I ran with the button for every race to emphasize this is what it’s about. It’s about human rights. It’s not about Black rights or Asian rights. It’s about humanity. It’s about all people’s rights.”

Then, just 10 days before Mexican president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz opened the Olympic Games, students in Mexico City were violently attacked during a protest intended to shine the spotlight on Ordaz’ authoritative regime. The rally sought a halt to state violence, accountability for police and military abuses, the release of political prisoners and free speech.

The peaceful protest of unarmed students was broken up by Mexican military troops, snipers and police officers who fired into the crowd killing as many as 300 people (official estimates of the dead still remain uncertain). The incident intensified the sprinters’ resolve to make a political statement at the Olympics.

“We decided that it was up to each of us to figure out how we wanted to make our voices heard, “ Smith said. “I knew if I did nothing, there would be no chance to make any progress. I couldn’t do nothing.” (from Raise a Fist, Take a Knee: Race and the Illusion of Progress in Modern Sports, John Feinstein)

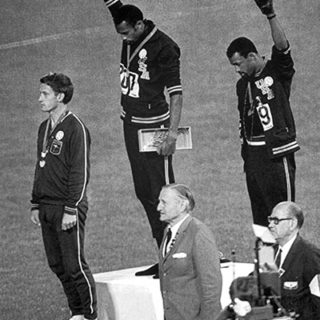

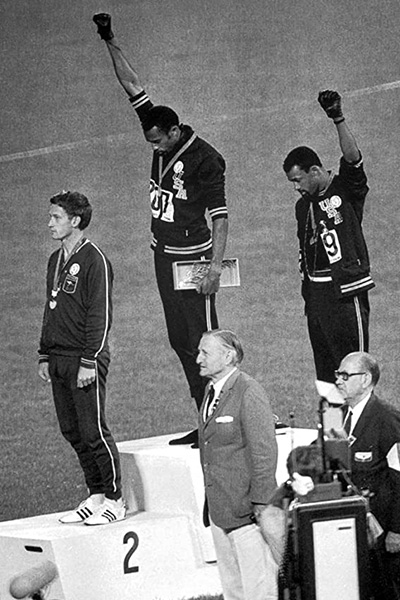

On October 15, 1968, just two weeks after the protesting students were shot down in Mexico City, the gun sounded to begin the 200-meter dash featuring Smith and Carlos. Smith sprinted away with the gold medal in a world record time of 19:83. Australian Peter Norman won the silver. Carlos captured the bronze.

As the medal ceremony was about to begin, Smith and Carlos appeared on the podium shoeless and in black socks to symbolize the poverty many Black people experience in the United States. On their USA track uniforms they displayed OPHR (Olympic Project for Human Rights) buttons. Silver medalist Norman, who was keenly aware of what was about to take place, also wore an OPHR button to stand in solidarity with Smith and Carlos.

As the “Star-Spangled Banner” began to play, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised their black-gloved fists toward the sky. The resulting photo created one of the most visceral and transcendent moments in the history of the confluence of sports and the fight for equality. The nation watched the Black Power Salute as the 1968 Olympics marked the first time an American network broadcast the Games.

Smith later said the raised fists were never about a hatred for America but “a cry for freedom and for human rights…We had to be seen because we couldn’t be heard.”

The peaceful protest by Smith and Carlos had immediate repercussions. They were suspended from the U.S. Olympic team and forced to leave the Olympic Village. Back home in the USA they were subjected to death threats and many Americans considered them traitors. Employment opportunities and commercial endorsements wilted away.

According to Douglas Hartmann, author of Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete, Smith always indicated that the Black Power salute “stood for the community and power in Black America. He [Smith] didn’t want to be seen as a radical. He was far more of a kind of traditional American individualist. He was planning to go into the military. He was a patriot. He thought we needed to make a lot of changes on race, but it wasn’t necessarily from a radical political point of view.”

Evans, a third member of SJSU’s “Speed City,” went on to earn two gold medals at the 1968 games. He posted a world record time of 43.86 at the 400 meters. Later, he earned gold as the anchor leg in the 1,600 meter relay, which also set a world record. While accepting his gold medal in the relay, Evans and fellow African-American medalists Larry James and Ron Freeman wore black berets on the stand as a sign of protest.

The actions of the OPHR athletes struck a nerve in Black communities. The Black Power salute provided positive reinforcement for underprivileged individuals and engendered Black pride, racial identity and self-worth. The Black Power movement quickly became an influential part of popular culture, education and politics. The movement’s eye-opening challenge to inequality and discrimination inspired other groups, such as Women, Latinx, Native Americans, Asian Americans and LGBTQ+ communities.

“When we look at these athletes there are two things that we have to be aware of right out of the shoot,” Edwards said. “One, that they are absolutely superlative athletes. And the second thing is that they were very much aware of and committed to the struggle for freedom, justice, and equality, the struggle to form that more perfect union. Beyond that, I think that they were impressed by the fact that you didn’t just have to be an athlete. You could be an intellectual.”

In the years after the Olympic protest the impact of Smith, Carlos and Evans was recognized internationally. They were acknowledged as catalysts for change in America and abroad.

These Olympic athletes understood the power and gravity of their position as superior athletes and were growing their commitment to change. Athletes that are winners are then provided “with a great stage, that they can transform into a platform, whether it’s Smith and Carlos, whether it’s Kaepernick, whether it’s Ariyana Smith, whether it’s Simone Biles, whether it’s Megan Rapinoe,” Dr. Edwards said.

Decades later, the 1968 Olympic medalists were acknowledged for their efforts. By 2003, Smith, Carlos and Evans had all been inducted to the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame. In 2005 a statue was erected in honor of Smith and Carlos at SJSU. In 2008, Smith and Carlos were honored with the Arthur Ashe Award for Courage. And in 2016, President Barack Obama provided recognition for Smith and Carlos at a White House ceremony.

“Their powerful silent protest in the 1968 Games was controversial, but it woke folks up and created greater opportunity for those that followed,” Obama said.

For more information:

Fists of Freedom: The Story of the ’68 Summer Games – HBO Documentary

The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World, Dave Zirin, John Wesley Carlos

Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and Their Aftermath, Douglas Hartmann

The Revolt of the Black Athlete, Harry Edwards

Not the Triumph but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete, Amy Bass

Raise a Fist, Take a Knee: Race and the Illusion of Progress in Modern Sports, John Feinstein

COACH WOODEN and ME, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

When Black American Athletes Raised Their Fists at the 1968 Olympics – HISTORY

https://www.voanews.com/a/usa_timeline-us-race-riots-1965/6190204.html

Diversifying Team Leadership

Diversifying Team Leadership

Diversifying Team Leadership

Before earning distinction as one of the most successful American athletes in history, the first post-segregation Black head coach of a major professional sports team and an important civil rights advocate, Bill Russell was just another West Oakland kid attempting to make the McClymonds High School basketball squad.

Although tall and athletic, Russell initially struggled with basketball fundamentals and received just one college scholarship offer. The University of San Francisco saw potential in the lanky teenager equipped with a warrior’s persona, and Russell joined K.C. Jones and Hal Perry on the first major college basketball team to start three Black players.

With Russell at center, the USF Dons won the 1955 and 1956 NCAA championships and strung together 55 consecutive victories. It was the start of a legendary career that combined sports excellence and social justice advocacy.

Russell soon took his winning ways to the NBA, but not until he led the 1956 U.S. Olympic basketball team to a gold medal. When he finally reported to the Boston Celtics he guided them to a phenomenal 11 NBA championships.

Russell earned his first coaching position in 1966-67 as head coach/player for the Celtics. The following season he became the first Black coach to win an NBA title by leading Boston to victory over a Los Angeles Lakers team that featured future Hall of Famers Jerry West and Elgin Baylor. In 1968-69 Wilt Chamberlain joined West and Baylor with the Lakers and Russell’s Celtics beat them again for the NBA title. During his three seasons as coach of the Celtics, Russell’s teams compiled a stunning .661 winning percentage and captured two NBA crowns.

“But for all the winning, Bill’s understanding of the struggle is what illuminated his life,” his family stated at his passing in 2022, “From boycotting a 1961 exhibition game to unmasking too-long-tolerated discrimination … to decades of activism ultimately recognized by his receipt of the Presidential Medal of Freedom … Bill called out injustice with an unforgiving candor that he intended would disrupt the status quo.”

One of Russell’s first public examples of social activism occurred in October 1961 when the Boston Celtics were in Lexington, Kentucky to play a preseason exhibition contest. Prior to game time, Sam Jones and Tom “Satch” Sanders, both Black players for Boston, were denied food service at a local hotel. In protest, Russell, Jones and Sanders refused to play in the game. It was the first boycott of a sporting event over civil rights, according to the Basketball Network.

Russell continued to express his thoughts on civil rights when he marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Washington D.C., then sat near MLK as he gave his “I Have a Dream” speech.

In 1967, when boxing legend Muhammad Ali refused military induction during the Vietnam war as a conscientious objector, Russell joined several prominent Black men in Cleveland to meet with the heavyweight champion and offer support for his decision.

For his dedication and activism on behalf of civil rights, President Barack Obama presented Russell with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in a ceremony at the White House in February 2011.

Russell’s incredible playing career was honored in 1975 when he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Then, in 2021, he was inducted into the Hall of Fame a second time for his coaching career.

In 2022, Russell received the NBA’s ultimate honor when the league retired his #6 jersey league-wide, the only player in NBA history to receive the honor.

In 1979, Bill Walsh was hired as the head coach of the San Francisco 49ers, the first NFL head coaching position for the San Jose State graduate and Stanford head coach. At the time there were no Black head coaches in the NFL and less than half a dozen Black assistant coaches in the league. Walsh immediately hired two Black men to their first NFL coaching jobs: Dennis Green and Billie Matthews. Within three years Walsh also provided Ray Rhodes, Milt Jackson and Sherman Lewis with their initial NFL coaching positions.

“Bill Walsh just wanted the best people,” said Dr. Harry Edwards, Professor Emeritus of Sociology at U.C. Berkeley and a 49ers consultant. ”It didn’t matter if they were polka-dot or purple.”

Walsh’s inclusive eye for talent yielded success for the 49ers and the minority coaches he mentored. Green was eventually hired by the Minnesota Vikings in 1992 as just the second African-American head coach (after the Raiders Art Shell-1989) of the post-segregated NFL era. The Philadelphia Eagles hired Rhodes in 1995 as the NFL’s third Black head coach. He was named NFL Coach-of-the-Year in his first season at the helm. Matthews, Lewis and Jackson rose to the position of offensive coordinator in the NFL.

“I believe coaching, in a sense, represents the participants,” Walsh later said in a USA TODAY interview. “The racial-ethnic balance in football has turned over very rapidly in recent years, as has the interest and the involvement of so many men for the coaching profession. But we’re not seeing the upward mobility that we should be seeing.”

Walsh hired Dr. Edwards in 1985 as a consultant advising players, coaches and staff on race relations and social issues. In so doing Walsh brought the foremost thinker in the field of sports and social justice into the 49ers’ fold.

“While talking about a contract we discussed what we could do for one another,” Edwards said. “We were both following the same road on social issues. This gave me the opportunity to help and get inside the organizations I had been critical of and work with them.”

Edwards’ initial role quickly expanded and Edwards organized programs on life management skills and financial planning for young players. Veterans considering retirement were offered clinics on post-career opportunities. The programs he developed for the 49ers soon were adopted by the entire NFL. Eventually the Golden State Warriors and Major League Baseball sought Edwards’ counsel on player personnel matters and on increasing front office opportunities for people of color.

Throughout his career Walsh generously offered his time to aspiring young coaches. He was a frequent speaker at clinics for high school and college coaches, and made a habit of inviting minority coaches to 49ers training camps to observe his methods. Walsh already had two Super Bowl rings and was working on his third in 1985 when he felt more could be done to increase the lack of minority coaches in the NFL.

By 1986 Walsh was ready to offer a more formalized approach to his coaching clinics and The Bill Walsh NFL Diversity Coaching Fellowship was born. It began as a collaborative effort between Walsh, Edwards and 49ers public relations executive Rodney Knox. They also had the unfettered support of team owner Edward DeBartolo Jr. and vice president John McVay.

The primary goal of Walsh’s fellowship was to provide talented minority coaches the opportunity to work alongside the 49ers staff and expose them to NFL practice methods, training techniques and offensive and defensive philosophies. Graduates of the program would receive formal evaluations and letters of recommendation.

“Bill (Walsh) had a strict set of ideals and standards he used to evaluate candidates for admittance to the program,” Edwards said. “He was looking for bright coaches with the ability to teach and who exhibited ‘executive command.’”

According to Edwards, Walsh’s definition of executive command meant they possessed:1. Respect – gained through technical proficiency and a clear grasp of a designated coaching discipline; 2. Affection – the skill to push others to do more than they believe is possible; and 3. Authority – the ability to ensure that the appropriate standards are met.

The program also offered participants a myriad of networking opportunities. In the up-and-down world of football, a coach’s career depends on connections. The fellowship provided numerous up-and-comers the chance to openly exchange ideas.

Lovie Smith was a college linebackers coach when he attended one of Walsh’s first fellowship programs. He claims the exposure he received redirected his career and in 2004 the Chicago Bears hired him as their head coach. Two years later, he guided the Bears to Super Bowl XLI where he and opposing head coach Tony Dungy (another Walsh protege) of the Indianapolis Colts were the first African-American head coaches to face off in the Super Bowl.

“I am a big believer in what it can do for young college coaches who are searching for an avenue into our league,” Smith said of the minority coaching fellowship. “As a participant in the program, I learned so much about what goes into the business on the professional level. The experience and networking opportunities that I had during my time had a very big impact on my career path.”

Smith is one of a bevy of future head coaches who used the fellowship as a springboard to the NFL. Other participants include Marvin Lewis, Leslie Frazier, Mike Tomlin, Hue Jackson, Anthony Lynn and Raheem Morris, all graduates of the program who went on to become NFL head coaches. Tyrone Willingham, a head coach at Stanford, Notre Dame and Washington was another participant.

Tomlin led the Pittsburgh Steelers to a Super Bowl title in 2008. At the age of 36, he was the youngest head coach to win a Super Bowl ring until the Rams’ Sean McVay’s Super Bowl victory in 2021. Entering his 16th season with the Steelers Tomlin has never recorded a losing season.

Katie Sowers, a 49ers assistant coach from 2017-2020, is the first female openly gay coach in NFL history. After working for the Atlanta Falcons, she began her career with the 49ers after earning a spot on the staff as part of the Bill Walsh Diversity Coaching Fellowship in 2017. After working as a seasonal offensive assistant for two years she was hired as a full-time offensive assistant in 2019. The 49ers won the NFC championship that season and advanced to Super Bowl LIV where Sowers established herself as the first woman to coach in a Super Bowl.

The Bill Walsh coaching universe is well-known throughout football. An astounding 17 Super Bowl winning teams have been led by a member of the Walsh coaching line. But by providing coaching opportunities for minorities his impact on football is further amplified. According to Dr. Edwards, Walsh was “one of the greatest influences on social issues in sport in the past half-century.”

“He was THE brightest person I ever met,” Edwards said. “He was also one of the greatest teachers and a man of compassion. He would go out of his way to help players, coaches, friends who were in need. He once told me if we don’t look out for one another we have nothing.”

The concepts introduced by Walsh and Edwards continue to resonate throughout the NFL. The programs they pioneered became the model for a league-wide initiative that now includes all 32 NFL clubs. Their shared vision on social justice and equality, whether on the athletic field, in the classroom or in executive offices, helped open a new path for modern athletes and coaches.

The Bill Walsh NFL Diversity Coaching Fellowship soon became the standard followed by other collegiate and pro teams to attract minorities to leadership roles.

The Oakland (now Las Vegas) Raiders celebrate a long history of creating opportunity. In 1979 Raiders owner Al Davis hired Tom Flores as just the second Hispanic head coach in the NFL (after Tom Fears 1967-1970, N.O. Saints).

Flores, the son of a Mexican immigrant father from Durango and a first-generation mother from Jalisco, was the first NFL coach with Mexican roots to win a Super Bowl in 1980. Three years later he led the Raiders to another championship at Super Bowl XVIII. Flores also earned a Super Bowl ring as an Raiders assistant coach in 1976. He was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2021.

Davis also hired the first Black head coach in the NFL’s modern era when he named Art Shell, an eight-time Pro Bowl tackle with the Raiders, as the head coach. In 1990, Shell was named the NFL’s Coach of Year.

Amy Trask was appointed by Raiders owner Al Davis in 1997 as the NFL’s first female non-owner CEO. She began her tenure with the Raiders in 1983 as an intern in the club’s legal department and moved through the front office ranks before serving as the Raiders CEO for 15 years until 2013.

In 2022, the team named Sandra Douglass Morgan the NFL’s first ever Black woman team president.

The Golden State Warriors were early trailblazers in hiring under-represented groups to leadership positions. In 1968, Franklin Mieuli, owner of what was then called the San Francisco Warriors, named veteran guard Al Attles as a player/assistant coach under head coach George Lee. Known as “The Destroyer” because of his penchant for hard-nosed defense, Attles was a dynamic on-court leader when he assumed the Warriors head coaching position midway through the 1969-1970 season. He joined Boston Celtics legend Bill Russell, who was hired by the Celtics in 1966, as the second Black head coach in NBA history.

In 1975, Attles led the Warriors to the NBA championship, just the second Black NBA coach (after Russell) to earn an NBA title. After retiring as the Warriors skipper in 1983 with 588 career wins (including playoffs) under his belt, Attles moved into the franchise’s front office and never left. Attles has served the Warriors as a player, coach and team executive for over 60 years, believed to be the longest uninterrupted streak of any person for one NBA team.

Mieuli recorded another NBA milestone in 1969 by selecting the first woman in the NBA Draft. In the years prior to the passage of Title IX, the Warriors picked Denise Long, a high school senior from Iowa, in the 13th round of the NBA Draft. Unfortunately, league commissioner Walter Kennedy had other ideas. He vetoed the Warriors pick claiming the NBA is not allowed to select high school players, nor does it draft women.

Despite Kennedy’s rebuff, Mieuli was committed to women’s professional basketball and organized his own four-team league. The women’s teams played their games before the Warriors contests and often put on exhibitions at half time. Mieuli also took Long under his wing and helped pay her tuition at University of San Francisco.

Continuing the organization’s leadership, Rick Welts joined the Golden State Warriors as president and COO in 2011 not long after coming out as gay in an interview with The New York Times. He was the first prominent American sports executive to come out as openly gay. During his time with San Francisco, he helped turn the Warriors into a perennial contender, winning four NBA titles since 2015.

The San Francisco Giants have a legacy of inclusion on the baseball diamond and in the coaching ranks. During their inaugural season on the west coast the Giants opened the 1958 campaign with, clearly, the most racially diverse roster in Major League Baseball.

At a time when most clubs employed 2-3 minority players at best, over 35 percent of the Giants roster consisted of people of color. And, in the Giants 1958 opening game shutout of the L.A. Dodgers, they featured five Black or Brown players in the starting lineup.

The Giants roster included future Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda and fellow Puerto Rican natives catcher Valmy Thomas and pitcher Ruben Gomez, all opening day starters. OF Felipe Alou, who was born in the Dominican Republic, played six seasons in San Francisco and later was joined in the outfield by his brothers Matty and Jesus. Venezuelan born starting pitcher Ramon Monzant posted an 8-11 record in 1958. Bahamian native Andre Rodgers provided a bat off the bench and slick glove as a utility infielder.

And the heart of the Giants lineup consisted of several African-American stars including Willie Kirkland, Bill White, Leon Wagner and the incomparable Willie Mays, one of the greatest players of all time. White, a first baseman, began his career with the New York Giants and was part of the franchise from 1956-1958. He went on to become the National League president from 1989-1994.

The Giants pedigree as a progressive-minded employer led to several important coaching hires by the club, including Frank Robinson (a basketball teammate of Bill Russell at McClymond’s HS) as manager in 1981. Robinson earned distinction as MLB’s first Black manager in 1975 after being hired to lead the Cleveland Indians. Giants owner Bob Lurie pursued Robinson and signed him to manage San Francisco from 1981-1984.

Peter Magowan took over as team president in 1993 and hired Dusty Baker as San Francisco’s second Black manager. In his first season at the helm, Baker led the Giants to an incredible 103 wins but the Atlanta Braves won 104 to nudge San Francisco out of the playoffs.

Magowen also hired Felipe Alou, the team’s first Latino manager to replace Baker from 2003-2006. Alou guided the Giants to the 2003 National League West title and coached his son, Moises, in San Francisco in 2005 and 2006.

While the Bay Area has been home to many significant examples of what sports organizations can do to create space for the people of color who belong in its executive and coaching ranks, there is still a long way to go in creating true equity.

To engage this topic further, check out:

PRO Sports Assembly – https://www.prosportsassembly.org

Fritz Pollard Alliance foundation – https://fritzpollard.org

Bill Walsh Diversity Coaching Fellowship – https://operations.nfl.com/inside-football-ops/players-legends/nfl-player-engagement/support-for-players-on-and-off-the-field/bill-walsh-diversity-coaching-fellowship

Nunn-Wooten Scouting Fellowship – https://operations.nfl.com/inside-football-ops/players-legends/nfl-player-engagement/support-for-players-on-and-off-the-field/nunn-wooten-scouting-fellowship/

Sexism & Equal Opportunity

Sexism & Equal Opportunity

Sexism & Equal Opportunity

Title IX was signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1972. It reads, “No person in the United States shall, based on sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

That 35-word sentence changed the athletic landscape. It banned sex discrimination in education and allowed girls and young women access to sports, and other educational programs, that were previously available only to men.

Ironically, Title IX did not specifically address equality in sports. It sought to fight discrimination against women in federally funded academic settings. Eventually it grew to encompass athletics and helped bridge disparities beyond the classroom.

Title IX prompted an increase in the number of females participating in organized sports at all levels from grade school through college. It also established a clearer path for women to earn scholarships, continue involvement in professional, amateur and collegiate sports and gain access to executive positions

As the 20th century drew to a close, equal opportunities for women in sports gradually moved forward. According to the Women’s Sports Foundation, in 2022, 50 years after the landmark Title IX legislation was passed, nearly 3.5 million high school girls were involved in a sport, nearly two of every five females. Prior to Title IX’s passage in 1972, there were less than 300,000 high school female sports participants, just one of every 27 women. In addition, more than 190,000 women were competing in intercollegiate sports—six times as many as in 1972.

According to Neena Chaudhry, general counsel and senior advisor for education at the National Women’s Law Center, research shows that in addition to physical health, girls who play sports are more likely to have higher levels of self-esteem, stronger collaborative skills, and greater academic achievement. But disparate access to athletics, through both community centers and the rising cost of youth sports, makes schools a key place to engage young girls of color in athletics.

Today, Title IX is best known for its legacy in growing athletic opportunities for women.

But just months after Title IX was signed into law, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its landmark Roe v. Wade decision granting women the right to choice. Title IX and Roe v. Wade are fundamentally intertwined.

In 2021, nearly 500 female athletes, including soccer star Megan Rapinoe, WNBA veteran Sue Bird, Olympic gold medal swimmer Crissy Perham, and basketball standout Brittney Griner, submitted a brief to the U.S. Supreme Court in support of a woman’s right to choice. A major part of their argument was that the success of females in sports depends on having control over their own bodies.

It’s “a deeply-held belief that women’s athletics could not have reached its current level of participation and success without the constitutional rights recognized in Roe v. Wade,” the brief states, and “Without Roe’s constitutional protection of women’s bodily integrity and [decision-making] autonomy, women would not have been able to take advantage of Title IX and achieve the tremendous level of athletic participation and success that they enjoy today.”

Their message was clear. No woman can enjoy the rights provided by Title IX without the ability to make their own choices about their own bodies. But the road to equality has been a long and arduous process. Listed here are some of those landmark moments.

Evolution of women’s sports

1963 – Congress passes the Equal Pay Act after lobbying from Eleanor Roosevelt and the Commission on the Status of Women. They also urge federal courts that “the principle of equality become firmly established in constitutional doctrine.”

1964 – The Civil Rights Act bans sexual discrimination by employers and creates the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

1964 – Hawaii’s Patsy Mink is the first woman of color elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She later co-authors Title IX, the Early Childhood Education Act and the Women’s Educational Equality Act.

1966 – The National Organization for Women is established and addresses the need for women to have “full participation in the mainstream of American society … in equal partnership with men.”

1971 – The Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) is founded as a governing board for collegiate women’s sports.

1972 – Congress passes Title IX and it’s signed into law by President Richard Nixon.

1973 – The Supreme Court decides in the landmark decision Roe v. Wade that the states do not have an unfettered right to curtail abortion, effectively protecting women’s right to choose.

1973 – Women’s tennis star Billie Jean King soundly defeats Bobby Riggs in the “The Battle of the Sexes” tennis match.

1974 – The Women’s Educational Equity Act provides financial assistance to institutions struggling to meet Title IX requirements.

1975 – President Gerald Ford recognizes the need for gender equality in sports and signs Title IX athletics regulations. He states “it was the intent of Congress under any reason of interpretation to include athletics.” Athletic departments have up to three years to implement the rules.

1976 – The NCAA files a lawsuit challenging the athletic components of Title IX. It is dismissed two years later.

1979 – UCLA basketball star Ann Meyers signs with the Indiana Pacers becoming the first woman to sign an NBA contract.

1982 – In the first NCAA Women’s Basketball Championship game, Louisiana Tech defeats Cheyney State.

1984 – The U.S. wins its first Olympic gold medal in women’s basketball.

1985 – Tara VanDerveer becomes Stanford Women’s Basketball head coach. She has led the Cardinal to three NCAA titles and is the winningest coach in women’s college basketball history. She also is a member of the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame.

1988 – Congress overrides President Ronald Reagan’s veto of the Civil Rights Restoration Act, making it mandatory that Title IX apply to any school that receives federal money.

1997 – The Women’s National Basketball Association begins play.

1999 – Brandi Chastain boots a dramatic penalty kick to give the U.S. a win over China in the World Cup final.

2001 – Jacksonville State kicker Ashley Martin becomes the first woman to play and score in a Division I football game.

2014 – The NBA San Antonio Spurs hire Becky Hammon to be the first female full-time assistant coach in any of America’s major professional sports.

2021 – A legal report from New York law firm Kaplan Hecker & Fink LLP criticizes the NCAA for prioritizing its Division I men’s basketball tournament over women’s championship events.

2022 – The U.S. Soccer Federation agrees to pay its men’s and women’s national teams equally, becoming the first governing body to promise matching funds for both sexes.

2022 – The Supreme Court overturns 50 years of precedent set by Roe v. Wade in the Dobbs decision.

Brandi Chastain, a San Jose native, provided one of the defining moments in the annals of women’s sports. She earned two Olympic gold medals as a USA soccer player and competed on two FIFA Women’s World Cup championship teams. In the 1999 FIFA World Cup final against China, Chastain drilled home the winning penalty shootout goal then dramatically dropped to her knees and pulled off her jersey.

The resulting Sports Illustrated cover photo of Chastain kneeling on the field in a sports bra with her arms raised in joyful victory became an iconic image. It highlighted a transcendent moment that resonated with both women and men, and captured the attention of Americans and citizens abroad. It showcased a female athlete for the first time globally in the same manner as men: exhausted and victorious on a global stage.

In the leadup to the game, ABC television commentator Robin Roberts tried to describe the electricity that surged through the 90,000 fans at the Rose Bowl that day, an event that broke attendance and television records for women’s sports.

“What we are seeing clearly transcends sports,” Roberts said. “This is a moment in American culture … embracing women athletes in this magnitude. And the athletes themselves realize they are part of something special.” However, as images of the moment circled the globe the act of disrobing became an instant flashpoint. Men removing their shirts on soccer pitches was an expression of power and celebration. But a woman? Many saw the identical gesture as provocative and unbecoming.

Chastain embraced being a role model for women and girls around the world. In 2005 she and teammate Julie Foudy co-founded the Bay Area Women’s Sports Initiative which, among many other initiatives, provides free after school fitness and confidence building programs for young girls, primarily those living or going to school in under-resourced communities. Over 20,000 girls have been served to date. After retiring from soccer in 2010 she focused on coaching and developing young players.

Amy Trask was appointed by Raiders owner Al Davis in 1997 as one the NFL’s first female CEO’s. She began her tenure with the Raiders in 1983 as an intern in the club’s legal department and moved through the front office ranks before serving as the Raiders CEO for 15 years until 2013.

Most recently, in July 2022, Mark Davis, the son of Al Davis and now the controlling owner and managing general partner of the Las Vegas Raiders, hired Sandra Douglass Morgan to be the club’s new president. Morgan is the first Black woman to be hired as an NFL franchise’s president. Prior to taking command of the Raiders, Morgan, a Las Vegas attorney, served as chairwoman and executive director of the Nevada Gaming Control Board.

Davis’s hiring of Morgan was met with approval in Las Vegas and sparked excitement among Raiders players and coaches.

“It’s incredible,” defensive end Maxx Crosby said. “First off, just breaking barriers. Mark (Davis) has done an incredible job and it started with his father. You know, just being transparent and giving everyone an equal opportunity. She’s honestly the best for the job and it’s going to be awesome, we’re excited for the future.”

Mark Davis, continues to support equal employment opportunities for women in other venues. In 2021 he purchased the Las Vegas Aces of the WNBA and installed several Bay Area women to leadership positions. Among them are Jennifer Azzi, a former basketball star at Stanford, the University of San Francisco Women’s Basketball head coach, and now the Aces’ director of business development.

Davis also hired coach Becky Hammon to a league-record salary of over $1 million. Nikki Fargas, the former head basketball coach at LSU is the Aces’ team president.

Katie Sowers, a 49ers assistant from 2017-2020, was the NFL’s second full-time woman coach, and first openly gay coach. She began her professional career in 2016 as an intern with the Atlanta Falcons working with receivers under offensive coordinator Kyle Shanahan. A year later Shanahan was named head coach of the 49ers and Sowers was awarded a spot on the staff as part of the Bill Walsh Diversity Coaching Fellowship.

“I credit Kyle a lot, “Sowers said. “He’s not the type of guy that’s gonna just hire people just to hire people. He wants quality people regardless of their gender, their race. And so, you know, I was blessed to kind of be in that category of people for him.”

After working as a seasonal offensive assistant for two years she was hired as a full-time 49ers offensive assistant in 2019. San Francisco won the NFC championship that season and advanced to Super Bowl LIV where Sowers established herself as the first woman to coach in a Super Bowl. Those experiences provide her with a unique perspective to observe the difficulty of women breaking into the upper ranks of the sporting world.

“I think that all too often we as women sometimes feel as though there is one seat at the table and we’re all fighting for that seat,” Sowers said. “There should really be room for everyone and we should be pulling up chairs.”

After the 2020 NFL campaign Sowers joined the staff of her twin sister Liz, who is the head coach of the Ottawa University (Kansas) women’s flag football team. After Ottawa won the first ever national championship for women, Sowers decided to remain on the staff and also will teach a college-level class on the methods of coaching football. For Sowers it’s all about the journey.

“Sometimes our dreams, they change, and they evolve with the way the world progresses,” Sowers said. “And for me, that evolution came with an opportunity to actually have more of a voice, more of a presence in the game of football…I felt like this was the path that was meant for me.”

Sowers admits there’s a long winding path ahead for women interested in sports

management careers or coaching but the 49ers are one NFL franchise that is helping pave the way.

“The game of football is evolving and it’s becoming more available for more people,” Sowers said.” Even though we do have a long way to go, you know, in terms of the unconscious and conscious bias that still exists in hiring and all of that. But, it’s really cool to see the steps that are being taken.”

Alyssa Nakken broke new ground in 2020 after being hired by the San Francisco Giants as the first full-time female coach in Major League Baseball. The former Sacramento State softball star and University of San Francisco student posted another MLB milestone on April 12, 2022 when she took the field as the Giants first base coach in a game with the San Diego Padres. She became the first woman to appear as an on-field coach in an MLB regular season game.

“I think people are able to see, not just women, but young men, men, young girls, women, everybody can just see that there are a lot of opportunities in baseball,” Nakken said in a post-game interview. “Not just in baseball. I think that sometimes we limit ourselves to thinking what we could do — at least that’s my experience. I never thought that I could do something like this.”

Before Nakken joined the Giants’ coaching staff, she worked in the baseball operations department, aiding with the team’s health and wellness programs. She also served in several front office roles after earning a master’s degree in sports management from USF.

For more information:

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/27/sports/soccer/title-ix-soccer.html

https://www.sfchronicle.com/sports/article/title-ix-womens-sports-17259612.php

Colin Kaepernick’s Impact and Influence

Colin Kaepernick’s Impact and Influence

Colin Kaepernick’s Impact and Influence

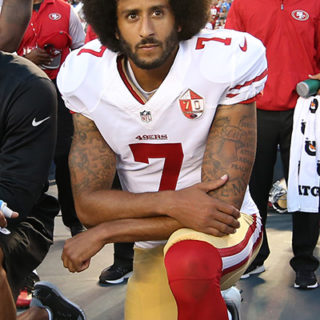

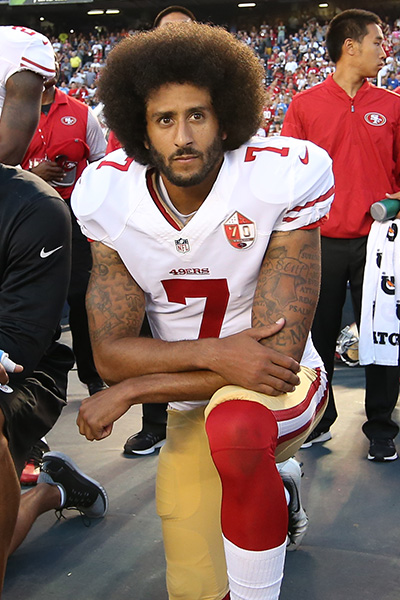

When 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick knelt down on one knee on September 1, 2016, he created one of the most iconic images of the 21st century. His likeness became a global symbol of resistance and non-violent protest against police brutality against people of color.

The country had seen a series of killings of unarmed Black men that summer, among them Alton Sterling and Philando Castille, and professional athletes were as concerned and outraged as others. WNBA players from three teams wore “Black Lives Matter” shirts despite being fined by the league; Cleveland Browns running back Isaiah Crowell posted an image of a police officer’s throat being slashed, accompanied by the words: “Mood: They give police all types of weapons and they continuously choose to kill us … #weak.”

Both incidents took place that July, as did the killing of five Dallas police officers. They were ambushed by a sniper who had expressed anger over the killing of unarmed Black men. Further fanning the flames of unrest was America’s polarization along political party lines as the general election between Democrat Hillary Clinton and surprise Republican candidate Donald Trump heated up.

Kaepernick’s protest began in August, when he sat on the bench during the National Anthem at each of the 49ers’ first three preseason games. Media took note for the first time on August 26, 2016 at a home game against the Green Bay Packers.

“I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses Black people and people of color,” Kaepernick told NFL Network reporter Steve Wyche after the game.. “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

The 49ers’ statement the following day read: “The national anthem is and always will be a special part of the pre-game ceremony. It is an opportunity to honor our country and reflect on the great liberties we are afforded as its citizens. In respecting such American principles as freedom of religion and freedom of expression, we recognize the right of an individual to choose and participate, or not, in our celebration of the national anthem.”

“We recognize the right of any individual to choose to participate or not participate in the national anthem and so does the league,” said coach Chip Kelly. “So, the league’s statement is they encourage them, but it’s not required to stand during the playing of the national anthem. So, it’s his right as a citizen.”

The public’s reaction was sharply divided. Some fans, media members, and public figures felt Kaepernick disrespected the country and its flag. Trump, after winning the presidency, turned up the heat by urging NFL owners to “fire” any player who refused to stand during the anthem.

“He sparked something,” said Antoine Bethea, a 49ers safety in 2016. “A lot of people wanted to sweep the problems he was identifying under the rug, or mask them, so for him to be vulnerable and risk his career to stand up was powerful.Throughout neighborhoods across America, in corporate offices, in sports leagues, everywhere … he sparked conversations that needed to be had.”

A RICH HISTORY OF ATHLETE PROTEST

Kaepernick’s iconic protest is part of a long lineage of athlete activism, including:

1951 – The University of San Francisco’s undefeated football team refused an invitation to play in the Orange Bowl after it was informed its two Black players, Ollie Matson and Burl Toler, would not be allowed to participate.

1961 – Bill Russell and three other Black players on the Boston Celtics boycotted an NBA exhibition game after they were refused service at a Lexington, Kentucky, restaurant.

1966 – World heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali refused induction into the U.S. Army due to his Muslim faith, and as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. He was stripped of his boxing title and threatened with imprisonment

1968 – American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos accepted their medals at the Mexico City Olympics, then each raised a black-gloved fist above their bowed heads to protest racial discrimination.

1970 – Curt Flood, a Major League Baseball outfielder for 15 seasons, filed an antitrust suit against the league to dissolve the decades-old reserve clause. He claimed that being owned by a baseball team was similar to “being a slave 100 years ago.” Although he lost the case before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972 and never played again, his case opened the door to economic freedom for all future MLB players.

1976 – The “Oscar Robertson Rule” goes into effect after the NBA and Players Association settled their lawsuit thereby eliminating the ‘option’ or ‘reserve’ clause in basic player contracts, paving the way for free agency.

– In a period of relative calm in the ongoing fight for racial reckoning, athletes across sports leveraged their power to build personal wealth and economic might which enabled a new wave of athlete activism.

1996 – Denver Nuggets guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf refused to stand during the National Anthem and was suspended without pay for one game by the NBA.

2012 – Miami Heat players _ including Dwyane Wade and LeBron James _ wore hooded sweatshirts before their game and posted a video on social media saying, “I Am Trayvon Martin”. They were protesting the killing of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black teenage boy who was shot to death in Florida.

2014 – After the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Knox College basketball player Ariyana Smith walked onto her team’s home court in nearby Clayton with her hands raised, then fell to the floor for 4½ minutes, symbolizing the 4½ hours Brown’s body lay in the street after he was killed.

– Before their home game against the Oakland Raiders, St. Louis Rams players Tavon Austin, Kenny Britt, Jared Cook, Chris Givens and Stedman Bailey jogged onto the field with their hands up to mimic the “don’t shoot” gesture for Michael Brown, who had been shot and killed by St. Louis police. The St. Louis Police Department demanded that the NFL discipline the players.

2014 – Cleveland Cavaliers teammates LeBron James and Kyrie Irving were among several NBA players who wore “I Can’t Breathe” T-shirts before their games, a reference to the last words of Eric Garner, who died in the custody of New York City police officers that summer4.

2014 – During player introductions before a game against the Bengals, Browns wide receiver Andrew Hawkins wore a T-shirt that read “JUSTICE FOR TAMIR RICE (and) JOHN CRAWFORD” on the front, and “THE REAL BATTLE OF OHIO” on the back. Rice, just 12 years old, and Crawford had recently been shot and killed by local police. The Cleveland Police Union requested an apology from the team.

2015 – New York Knicks star Carmelo Anthony marched with demonstrators in his hometown of Baltimore to protest the death of Freddie Gray, who suffered fatal spinal injuries while in police custody 11 days earlier.

2014 – Los Angeles Clippers players wear their warm-ups inside out in reaction to then-team owner Donald Sterling’s racist comments.

2016 – Members of the Minnesota Lynx, New York Liberty and Phoenix Mercury began wearing “Black Lives Matter” T-shirts to WNBA games to protest recent police shootings. Police unions took offense, and the league fined both the teams and the players. Liberty center Tina Charles took to Twitter to say she refused “to be silent,” prompting WNBA president Lisa Borders to rescind the fines and begin a dialogue with the players.“While we expect players to comply with league rules and uniform guidelines,” Borders said, “we also understand their desire to use their platforms to address important social issues.”

PROTESTS FOLLOWING COLIN KAEPERNICK

Kapaernick, whose decision to kneel rather than sit during the anthem stemmed from a meeting with Nate Boyer, a former Army Green Beret who suggested kneeling would be more respectful, inspired civil protests at all levels of athletic events, from high school to professional, and in both male and female sports.

In September 2016, one of the first athletes to take a knee after Kaepernick was Rodney Axon, Jr., a football player at Brunswick (Ohio) High School. Numerous high school teams followed Axum’s lead, including Auburn High School in Rockford, Illinois, Woodrow Wilson High in Camden, New Jersey, and Lincoln Southeast in Nebraska, among many others.

A few days after Axon’s protest, several NFL teams and individual players marked the start of the season by joining Kaepernick in protest, notably the Miami Dolphins, New England Patriots and Kansas City Chiefs.

In September, soccer star Megan Rapinoe garnered national attention by kneeling during the national anthem at an international match to show solidarity with Kaepernick. In 2022 she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and thanked the former 49ers quarterback for being “so brave and giving us all a path to use our voices and to step outside of ourselves.” (SF Chron, July 3, 2022, Killion)

After some criticism of Kaepernick’s action in conservative media, Tony Dungy, a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, a former Indianapolis Colts head coach and ex-49ers player, vocalized the feeling of many of the athletes. During an appearance on “Fox & Friends” in 2018 he said, “These guys are not unpatriotic. They’re not standing against our country. They’re kneeling against what’s wrong in the country.”

After the 2017 season, Kaepernick became a free agent but was not signed by any NFL teams. He filed a grievance against the NFL in November 2017 accusing the league’s 32 teams of colluding to keep him out of the league. He reached a settlement with the NFL in 2019. Kaepernick’s teammate Eric Reid also reached a collusion settlement with the NFL after he went unsigned following the 2019 season.

Sources and further reading:

Interview With Ariyana Smith: The First Athlete Activist of #BlackLivesMatter. David Zirin. The Nation. 19 December 2014.

https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/interview-ariyana-smith-first-athlete-activist-blacklivesmatter/

Colin Kaepernick explains why he sat during national anthem. Steve Wyche. NFL Media. 27 August 2016.

https://www.nfl.com/news/colin-kaepernick-explains-why-he-sat-during-national-anthem-0ap3000000691077

Athletes and activism: The long, defiant history of sports protests. Steve Wulf. The Undefeated. 30 January 2019.

https://theundefeated.com/features/athletes-and-activism-the-long-defiant-history-of-sports-protests/

‘I wanted to see what it meant to protest.” Michelle Smith. ESPNW. 15 December 2014

https://www.espn.com/womens-college-basketball/story/_/id/12032241/california-golden-bears-brittany-boyd-charmin-smith-join-protests-berkeley